By Brendan Hodge and JD Flynn, article originally published in The Pillar . View original article here.

The Archdiocese of Cincinnati announced this month a major restructuring initiative that could eventually close 70% of the 211 parishes in the archdiocese.

While headlines about parish closures and the declining number of priests in the U.S. are hardly new, the dramatic scope of Cincinnati’s plan is noteworthy — especially because it raises questions about the future of the Church across the U.S.

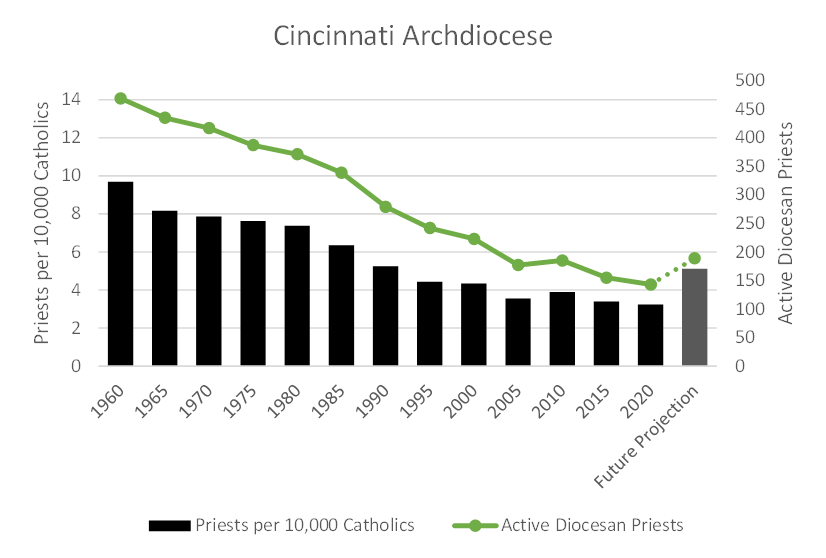

A quick look at the data shows why the archdiocese needed to take action.

In 2019, Cincinnati had 211 parishes but only 143 diocesan priests in active ministry, according to data collected by the Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate (CARA). That situation, the archdiocese has said, is not sustainable. Its plan is to group parishes together, assign priests to share pastoral duties, and gradually see parishes formally merged.

As the archdiocese begins its project, we at The Pillar found ourselves wondering: Is Cincinnati’s dramatic plan for parish closures a sign of what’s to come across the country, or is it responding to a problem unique to the Cincinnati archdiocese?

We looked at some numbers to find out.

A lot of parishes

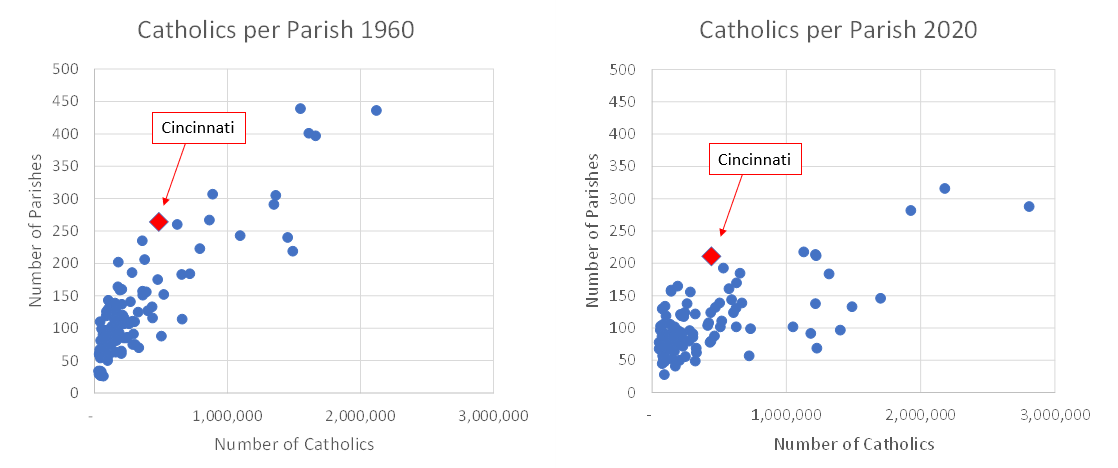

Given its size, the archdiocese has an unusually high number of parishes.

The Cincinnati archdiocese has the eighth-most parishes of any diocese in the U.S. Its 211 parishes follow closely behind Newark (212 parishes), Philadelphia (212), and Detroit (218).

But while Newark, Philadelphia, and Detroit each have more than one million Catholics, the Cincinnati archdiocese has only 442,000 Catholics.

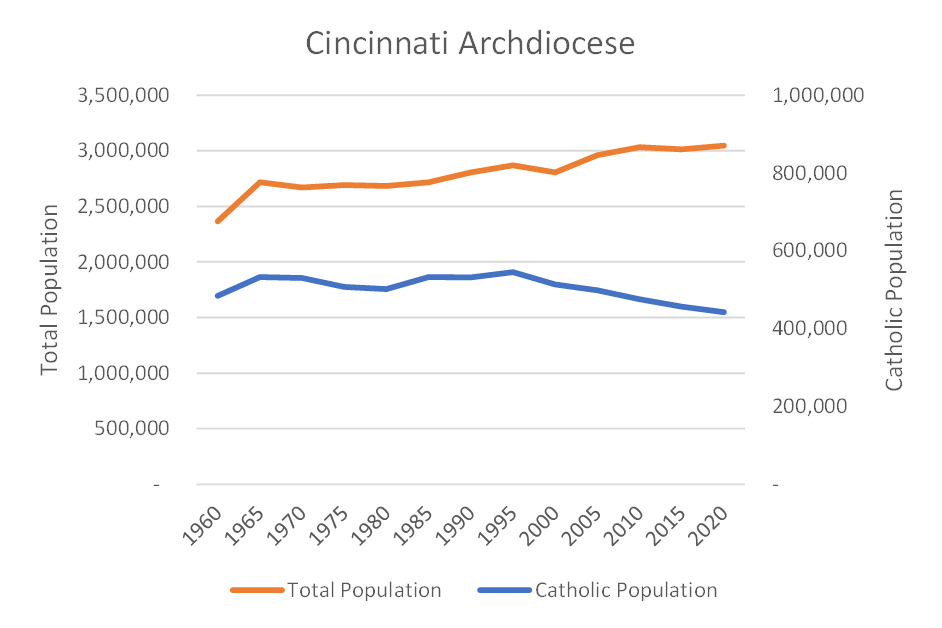

The disparity between the number of parishes and the number of Catholics is due, in part, to the changing demographics of the region. While the total population of the region has grown over the last 60 years, it is becoming less Catholic. The Catholic population of the archdiocese peaked in 1996 and has been dropping for the last 25 years.

At its peak, 19% of the region’s population was Catholic. At latest count that number has declined to 14.5%.

Sixty years ago, JFK was president, the first session of Vatican II had not yet begun, and the Baby Boom-fueled growth of the Catholic Church in the U.S. was in full swing. And the Cincinnati archdiocese already had an unusually high number of parishes: In 1960, Cincinnati had the ninth-most parishes, but its Catholic population was ranked 20th.

The Archdiocese of Cincinnati had 264 parishes in 1960, compared to 240 in Newark and 219 in Brooklyn. But Cincinnati had fewer than 500,000 Catholics that year, while Brooklyn and Newark each had more than 1.4 million.

For a diocese its size, why does Cincinnati have so many parishes?

The history of the region may be part of the reason. The archdiocese includes all of southwestern Ohio, encompassing both a number of rural areas and two cities: Cincinnati and Dayton.

Rural parishes often serve small numbers of Catholics, especially in those parts of the country in which parishes were established before widespread automobile ownership. (It was only in the 1940s that the number of U.S. households with a car reached 50%.)

Southwestern Ohio experienced dramatic population growth between 1900 to1960. Hamilton County, in which Cincinnati is located, doubled in population during those 60 years, and Montgomery County, containing Dayton, more than tripled. During the growth of that period, it might have seemed reasonable to the diocese to plan for ongoing growth in the years ahead.

Adding to the number of parishes, the archdiocese has been home to several large immigrant communities from

Catholic parts of the world. Because of cultural and language differences, German, Irish, and Italian communities often built separate parish churches in ethnic city neighborhood, often within blocks of each other.

That phenomenon is common in many East Coast and Rust Belt dioceses, and has led to parish closures in many of them, as mostly non-Catholics now live in many of those neighborhoods.

Populations move, churches stay in place

Within the Cincinnati archdiocese are counties which now have three times the population they did in 1960, and others which have shrunk.

Both Hamilton and Montgomery Counties, home to Cincinnati and Dayton, have fewer people than they did in 1960. At the same time, suburban and exurban areas have experienced dramatic population growth.

The result is that within the same archdiocese there are some parishes that once held hundreds of families every Sunday, and now see only a few dozen. At the same time, other parishes struggle to provide enough pews and parking for the people who come to Mass each week.

The local phenomenon is a microcosm of a broader national trend: The Cincinnati archdiocese is not the only place to discover the inconvenient fact that church buildings remain in place when people move elsewhere, both within a diocese, and at a macro-scale, between dioceses.

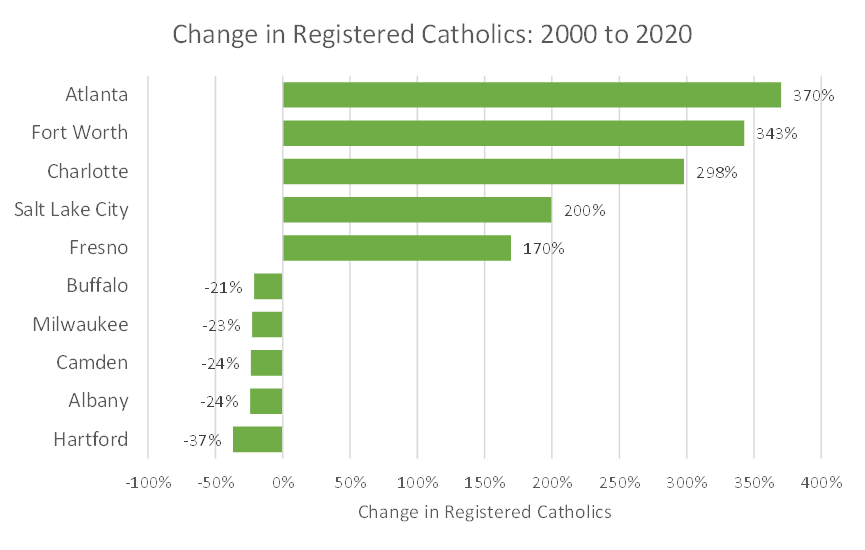

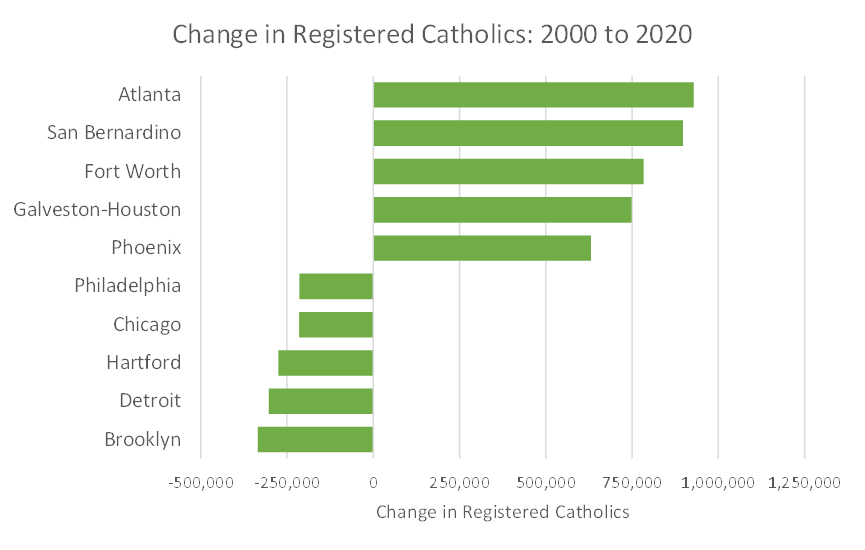

Across what is sometimes called the Rust Belt, several dioceses have seen their Catholic populations fall by more than 30% since 1960: Scranton, Syracuse, Youngstown, Buffalo.

At the same time, other dioceses have more than doubled in size during the last 60 years: Atlanta, Dallas, San Diego, and Houston have seen Catholic populations explode amid an overall national population shift toward the South and West.

In some ways, a Catholic attending Mass at an overflowing parish church in Dallas, who was baptized in a now-empty parish in Saginaw or Albany, is representative of the overall flow of Catholic population in America.

The result is that even as churches are closed or merged for lack of attendance in some areas, other places are building new churches for those who have moved within the U.S. or immigrated from outside the country.

But will those population shifts really mean that Mass attendance can be projected to grow in places with a growing Catholic population? Will suburban Ohio, or metro Houston, need to accommodate the same number of Catholics who once worshipped in shrinking cities like Cincinnati?

In the long term, that seems unlikely.

In addition to uncertainty about whether Catholics will return to Mass after the coronavirus pandemic, and growing institutional disaffiliation on the whole, demographic data indicates other challenges for the Church in the years to come, both in the Cincinnati archdiocese and across the country.

An aging population and shrinking parishes

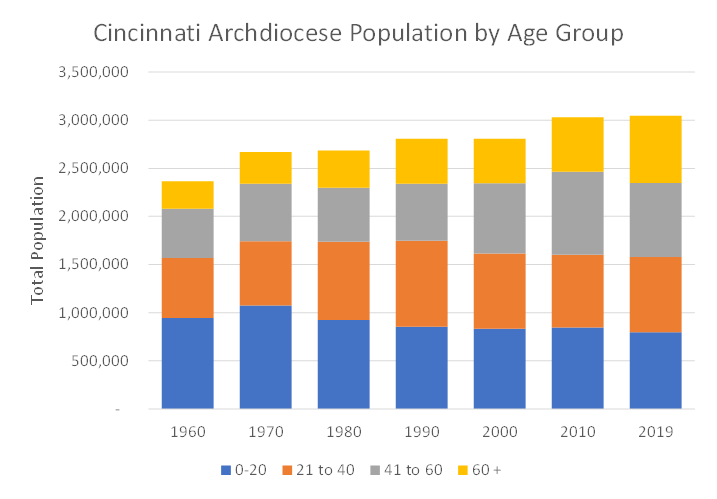

Like the rest of the U.S, the Cincinnati archdiocese has experienced demographic shifts as a result of falling fertility and increased lifespans. While the total population of the archdiocese has grown, the number of people under 20 reached its peak in 1970, and has been falling since then.

With a median age of 38, identical to the national average, the region has similar demographic patterns to many parts of the Midwest and Northeast. The total population of the Cincinnati region is increasing because of longer lifespans, but fewer children born mean a decreasing population is likely in the years to come.

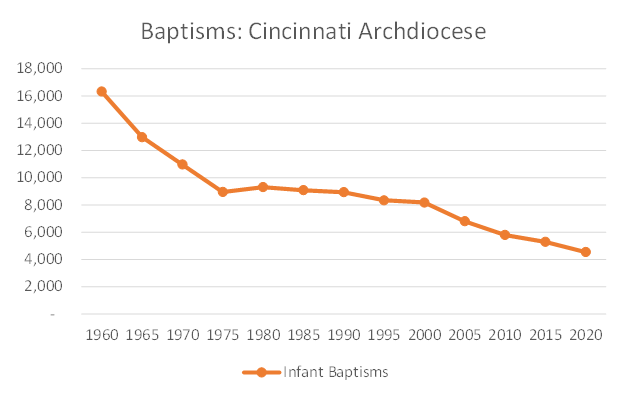

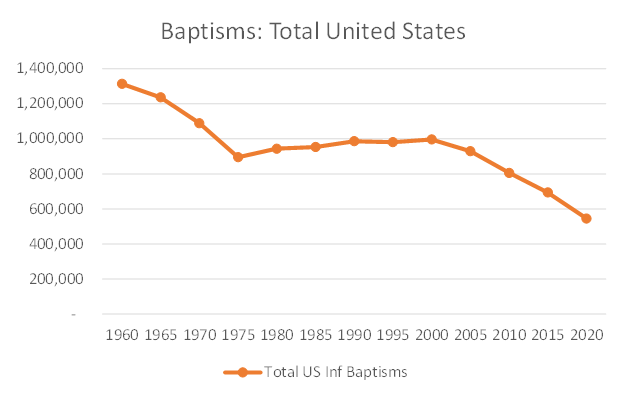

That change is reflected and amplified in the life of Catholic parishes. Recent generations have become less likely to actively practice their faith. In Cincinnati, like the U.S. as a whole, that means a decreasing numbers of parents have their children baptized.

Not Enough Priests, Not Enough Parishes

Shrinking dioceses tend to see shrinking numbers of vocations. And in many dioceses undergoing significant population growth, the number of registered Catholics per parish is already too large for one priest to realistically serve.

The Diocese of San Diego has 97 parishes for its 1.4 million registered Catholics; more than 14,000 Catholics per parish. Las Vegas, another diocese in which Catholic population has grown rapidly in recent years, has more than 20,000 Catholics per parish.

And yet many growing dioceses also face a shortage of priests. And ironically, some of the fastest growing dioceses will struggle to ordain enough priests for new parishes, even when they have a steady or growing number of seminarians.

Cincinnati’s experience offers a window into the Church’s situation across America.

Like many dioceses throughout the country, Cincinnati has seen a sharp decline in the number of priests in active ministry over the last 60 years. In 1960 the archdiocese had 469 diocesan priests in active ministry, while by 2020 that number was only 143.

Priestly vocations in the archdiocese have increased in recent years. The archdiocese has 60 seminarians in formation, and over the last five years it has ordained an average of 5.4 new priests per year.

The average age of American priests ordained in 2020 is 34. If Cincinnati maintains its current rate of vocations, and if the average priest is in active ministry for 35 years before retiring, Cincinnati’s number of active diocesan priests will increase from its current 143 to 189 in the coming years.

Other dioceses are in a similar position, with ordination rates suggesting the number of priests will grow in coming years. This effect is particularly strong in dioceses in which the Catholic population has grown significantly in the last 20 years. But for dioceses which have trouble already staffing parishes— whether because of population growth or a currently insufficient number of priests — the increase in numbers may not be enough.

According to CARA, the average newly ordained priest lived in his diocese for 17 years before entering the seminary. Once a priest is ordained in a diocese, he remains there typically for decades. The result is that it can take decades for the number of priests to catch up to the Catholic population in a rapidly growing diocese, even in a diocese with a strong focus on vocations.

The Archdiocese of Denver is experiencing that type of effect. The archdiocesan Catholic population grew from 373,500 in 2000 to 603,965 in 2020. With its current ordination rate of 6.2 priests per year over the last five years, Denver’s number of priests will likely increase from its current 140 active diocesan priests to around 217 priests in the coming decades. But with its rapidly growing population, Denver may well need to build more parishes.

While 200 priests would be sufficient to staff the 124 current Denver parishes, planners at the archdiocese would most likely find that adding parishes to accommodate population growth would put them in again in a hole in the future.

Other high-growth dioceses, like Houston, Dallas, and Austin will have more priests in the future than they do now, but will also need to assess carefully whether a prospective increase in priests will be enough.

In parts of the country with historically high Catholic populations, but where the number of Catholics has been shrinking in recent decades, diocesan leaders will face the opposite problem.

Chicago’s 487 active diocesan priests may be sufficient for the 316 current parishes of the archdiocese, but with an average of 8.2 ordinations per year, the number of active priests in the archdiocese will fall to around 287 in the coming decades, forcing tough decisions about parishes.

Similarly, Newark will likely see the current population of 375 priests fall to around 308 over the next few decades.

Such analysis assumes, of course, that all other factors impacting vocations and Catholic population will remain the same. Changes in fertility, immigration, faith formation, and the shifting culture will play out in ways that are harder to foresee. But the basic mission of the Church is to minister to all peoples. That means that as populations move, whether across town or across the continent, the Church will need to continue moving and adapting as well, if it is to bring Christ to the world.

And that, Fr. Del Staigers told The Pillar, is what the Cincinnati project aims to address.

‘It has to work’

Fr. Del Staigers is the pastor of St. Veronica Church and St. John Fisher Church in suburban Cincinnati — in a county that has grown considerably in recent decades.

But Staigers says that while his parish has seen population growth, participation in the parish and overall Mass attendance are on the decline. The priest said that the coronavirus pandemic has accelerated that decline.

“We’re about half to two-thirds of where we were in attendance on weekends [before Covid].”

Staigers said that when he surveyed his parishioners recently, he found that many people have not returned to Mass because they remain concerned about the pandemic, or they are caring for medically vulnerable loved ones. He said he does expect many to come back.

“I got no indication that people are staying away because they want to,” he said. “That’s the good news….I got no indication that people are saying ‘we’re mad at the Church and we’re leaving forever.’”

The priest noted high levels of engagement with the parish’s social service initiatives, and at the parish school.

At the same time, Staigers said that changes in the parish indicate a very different future for the Church in Cincinnati.

“I was telling my associate, who has had three weddings in two years, how different that is from when I was first ordained, in 1987 — it would be nothing to have one or two weddings a weekend for a while. And that’s just not the case, now.”

Without weddings, Staigers said, he’s not sure how many families will be active in the parish, or its school, where many of the most committed parishioners send their children.

Staigers said those changes indicate the importance of planning for the future.

“We’re like a lot of dioceses, in that we’ve got communities of people spread out that could be much more effective if we were pulled together more,” the priest added.

Staigers said parishioners in larger suburban parishes may not see the whole picture of the archdiocese, and that educating Catholics about the need to consolidate parishes and share resources will not be easy.

“They see the same three priests every weekend. They see churches that are reasonably full, active parishes, parking lots that can get crowded. They may not have the same sense as other parts of the diocese…that what they experience may not be what other parts of the diocese are seeing.”

“I’m guessing for the first three, four, or five years, it’s going to be a lot of heavy lifting for the clergy. I hope it gets lighter after that.”

Staigers told The Pillar that priests in the archdiocese have “a healthy dose of fear [about the consolidation project], because it’s so hard to see what this is really going to look like.”

He mentioned that previous efforts at pastoral planning in the archdiocese, most recently in the late 1990s, had not gained much support among the presbyterate.

Still, he said, he believes the effort could be good for priests. He said the initiative will invite laity to take on more responsibility for parish life.

“The paradigm is being shifted dramatically. And no matter what age, or how long you have been doing this, there is a sense of fear and uncertainty. ‘Cause we want it to work out. We know it’s got to change. No matter what age clergy members are, we know it’s got to change because we just can’t keep doing everything we’re doing.”

“I mean, I think if we’re smart about this, we’re going to engage a lot more parishioners to do a lot of the things that we’ve been doing,” he added.

Staigers recalled that when he was ordained in 1987, he imagined “I’d be a pastor in a suburban parish, and it would be stable and I’d have two associates.”

Instead, he said, he has multiple sites to serve. That’s “rewarding” in its own ways, he said. But “as we get, you know, thinner and thinner, spread out more and more, that’s harder and harder.”

“We’ve been spreading our priests out more and more. And now we’ve gotten to where we’ve realized we just can’t keep spreading this out, especially as the number declines.”

The burden priests face, Staigers said, is only one part of the challenges the Church faces. The numbers say the same. That, the priest said, is why Cincinnati, and many other dioceses, need to be sure they’re planning wisely for the decades ahead.

“I’m guessing most people are probably thinking that it is only because of a priest shortage. And that’s one part of it. That’s one little brick. It’s an important part, but it’s not the whole part.”

For the Church’s future in Cincinnati, Staigers told The Pillar, the consolidation process “has to work.”

For now, in his parish, Staigers is focused on gratitude.

“I’ve really been trying to focus on that whole stewardship mentality — that we realize how blessed we are. And so the only natural thing for us to do is to come together and give thanks.”

Brendan Hodge

Freelance writer